Paul Garber: A Man With Vision

Paul Garber: A Man With Vision

Paul Garber: A Man With Vision

Paul Garber: A Man With Vision

By: M. Robinson

Paul Garber’s life spanned an incredible era. He was born in 1899, just as powered flight was being developed. When he died, in 1992, man had already walked on the moon, and exploration of Mars had begun. Paul relished every single step in aviation history with passion, intrigue, and a twinkle in his eye.

Paul Garber actually appears to have been born with the specific purpose; that of nurturing, procuring, preserving, protecting, and then sharing, all things aeronautical. Aviation and the profusion of knowledge were deeply ingrained in his DNA. I can’t escape the feeling that Paul Garber picked up where Octave Chanute left off, as an eminent historian of flight.

His uncle gave him a kite for his 5th birthday and he did a version of traction kiting into the surf before the prophetic uncle snatched him up. Young Garber was still clutching the kite string in his chubby little hands as he was carried back to safety.

During Paul’s youth his family lived in Washington, DC on Connecticut Avenue, near the home of Alexander Graham Bell. With his propensity for crossing paths with history; Garber, as a child, received a kite-flying lesson from Bell. A story often told by Garber:

“He would walk by, six feet tall, with a white beard, black coat, very imposing. One day I was out front—we had a big yard—flying a kite. Well, Dr. Bell came along and said ‘That kite isn’t bridled properly’. He pulled it down and had me hold the kite while he re-bridled it, and sure enough when he launched it again it flew better. Then he patted me on the head.”

In

July of 1909 Garber witnessed an early flight demonstration that Orville Wright

was giving to the US military. In his own word’s Paul Garber recounts:

In

July of 1909 Garber witnessed an early flight demonstration that Orville Wright

was giving to the US military. In his own word’s Paul Garber recounts:

“Then it was in 1909 that I saw Orville Wright Fly. By That time, we’d moved to Washington. This particular morning in the newspaper I’d seen an account of Orville Wright Flying at Fort Myer, Virginia. So I asked my father if I could have some carfare—I think it was fifty cent round trip—and as I got out of the trolley car I could hear this sound. And here came this airplane. Well, I’d never seen and airplane before. It was like an enormous kite that had a noisy engine in it and two propellers whirling around and two men sitting in it. It came and flew overhead and then turned and went to the far end of the field and then came back again. I just stood there, transfixed.”

“Then I met a photographer. And I offered to carry one of his bags. Well that got me a little closer to the airplane, after it landed. I later learned that that the photographer was Winfield Scott Clime. I didn’t know who Orville and Wilbur were or who Charlie Taylor (their mechanic) was, but I realize now that those were the persons I was seeing.”

The Army purchased that airplane on August 2, 1909 making it the first military airplane in the world.

When Garber was 15 he made a glider based on the model of Octave Chanute’s man-carrying glider that was in the Smithsonian Institution. He initially flew the glider model as a kite. Then it occurred to Garber that a larger size would be suitable for taking rides. So Paul made it five times larger with a 20-foot span. He then gathered his neighborhood friends as well as all the clotheslines he could borrow, they went to a location with a downward slope (California & Massachusetts Ave) and upon instructions from Paul they began to run, pulling him into the air and towing him along. The glider was on his shoulders while he held onto the two struts that he had built onto it. It proved to be great fun and they repeated the glider flights a dozen or so times over the month.

That was it. The thrill of flight was in his blood and he was hooked for life.

Garber had an innate ability to gather information and then naturally dispense

it to others. As his interest grew in aviation, model airplanes were added to

his hobbies. While still in grammar school Garber started a club for kites and

model airplanes. Because of the club’s popularity it continued through high

school, as more and more students were eager to join.

Garber had an innate ability to gather information and then naturally dispense

it to others. As his interest grew in aviation, model airplanes were added to

his hobbies. While still in grammar school Garber started a club for kites and

model airplanes. Because of the club’s popularity it continued through high

school, as more and more students were eager to join.

Garber joined the Army in 1918 during World War I and was entering flight training at College Park, Maryland, when the war ended. After the war he began working for Air Mail Service, a fledgling enterprise.

In 1920, Paul Garber embarked on what would become his calling in life. It was then that he began his career of preserving aviation’s legacy at the Smithsonian Institution Museum. Garber was originally hired for a three-month temporary assignment; building models and preparing exhibits. He ended up staying for 72 years, devoting his life to the preservation of the nation’s aeronautical heritage.

In 1931, Garber became the Boy Scouts examiner for the aviation merit badge, stressing that the number one requirement was that the applicant should have made a kite that will fly. He also authored the book, Kites and Kiteflying.

Paul Garber worked in every area of the museum and was familiar with each phase of the operation. He completed his college education, married, and had three children; who he naturally taught to make and fly kites.

One day, after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Navy asked Paul Garber to use his expert knowledge to develop an aircraft recognition program. Garber entered the Navy as a Lieutenant (later Commander) in the Special Devices Division.

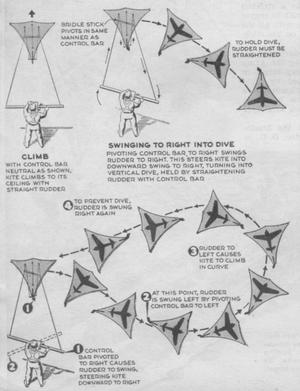

Shortly after the beginning of the war, Garber heard Admiral John H. Towers remark that one of the things the Navy needed the most was an improved moving target to speed up the training of aircraft gunners. Being an avid kite flyer, and kite historian, Paul thought that kites may be able to play a role in solving this problem. He knew production would be relatively easy and cheap, but it could not be a stationary kite; too easy of a mark. He had to find a way for the kite to do acrobatics and be able to dodge bullets.

Paul

Garber continued to think about how best to solve this problem as he followed

his initial orders - help with the production of millions of model airplanes

that were desperately needed by all divisions of the armed services for

recognition instruction.

Paul

Garber continued to think about how best to solve this problem as he followed

his initial orders - help with the production of millions of model airplanes

that were desperately needed by all divisions of the armed services for

recognition instruction.

Initially Garber worked on his target project in his own spare time with the help of fellow kite enthusiasts Stanley Potter and Lloyd Reichert, for almost a year.

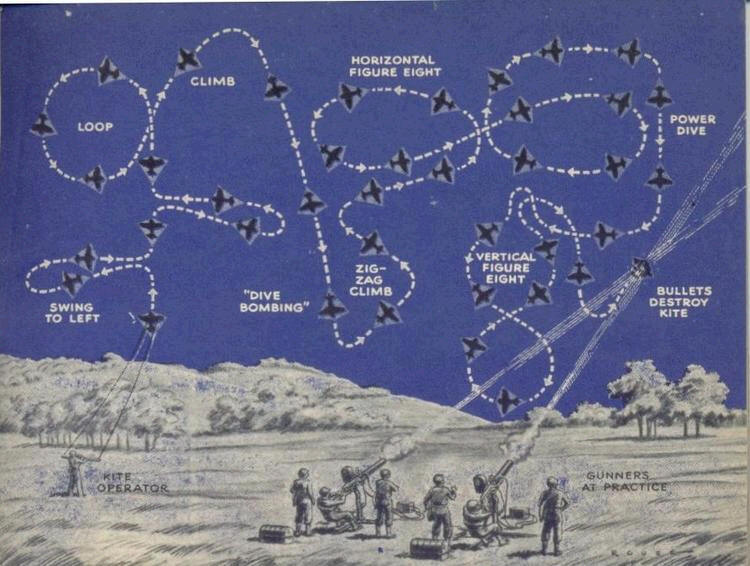

They started with a dual line Eddy kite-developed from a Malay design of a half-century earlier. The five-foot diamond kite had a rudder system for steering but no tail. The kite was designed to duplicate airplane maneuvers- loops, dives, figure eights, and was flown on 250 feet of line to simulate the size of an attacking plane.

When Garber was satisfied with the results of their research and development on the target kite, he arranged to demonstrate it for Captain (later Admiral) Luiz de Florez, head of the Special Devices Division of the Bureau of Aeronautics (Who was heard to have been muttering something about not having time to fly kites… There was a war on!)

Paul

Garber demonstrated the spectacular aerobatics of his target kite that day for

the military brass in DC. As if it was poetry in motion; Garber had the kite

flying over the Lincoln Memorial and Reflecting Pool from his position atop the

main Navy Department building roof in Washington. To add that personal touch,

Paul wrote out the name ‘Luiz’ with the kite and went back to dot the ‘i’.

Florez was said to have quickly admitted to Garber that his target kite was “The

best damn target I ever saw!”

Paul

Garber demonstrated the spectacular aerobatics of his target kite that day for

the military brass in DC. As if it was poetry in motion; Garber had the kite

flying over the Lincoln Memorial and Reflecting Pool from his position atop the

main Navy Department building roof in Washington. To add that personal touch,

Paul wrote out the name ‘Luiz’ with the kite and went back to dot the ‘i’.

Florez was said to have quickly admitted to Garber that his target kite was “The

best damn target I ever saw!”

The project was approved. Under Garber’s supervision over 350,000 target kites were made and distributed to sharpen the eye of anti-aircraft gunners. The target kites with Japanese Zeros or German FW 190 aircraft painted on them were delivered to all domestic and overseas bases, as well as all ships at sea.

Garber spent the remainder of the war working on the target kite assignment. Initially, the Navy contracted with the Comet model airplane firm, in 1943, to build 1200 kites and reels. Lt. Garber went to every gunnery station on the East Coast to demonstrate the kites. Garber set up kite flying schools for Navy personnel to learn how to fly the target kite.

Next Garber took his kites to the Navy’s PT Boat school in Melville, Rhode Island (where his son, Ned, was in training as a gunners mate). The leaders of the PT schools were thrilled with the kite’s abilities. One boat would fly a kite astern in evasive maneuvers while the other boats in the squadron tried to shoot it down as they roared along. Lt. Garber’s son became the school’s instructor in kite handling.

As Garber continued the tour of his kite demonstrations at gunnery stations, PT boat schools, and ships at sea, the Navy was easily convinced of the soundness of the project. The Navy placed a second order of 50,000 kites, this time from the sporting goods manufacturer Spalding. They followed that order up with two more purchase orders for 100,000 each. The target kites were produced for the price of $4.25 each.

At the end, of the war, Commander Garber received a commendation from the Navy for his kite work and contribution to the war effort, and in a show of gratitude the Navy released the target kite patents to him.

In

the end Paul Garber’s ingenuity was rewarded in the best possible way. When

Garber’s son Ned was in PT boat school he was assigned as instructor at the

Melville school. When Ned’s PT Boat was ordered out to sea he tried to get off

kite duty to join his boat. His skipper refused the request. The PT Boat was

lost with all hands.

In

the end Paul Garber’s ingenuity was rewarded in the best possible way. When

Garber’s son Ned was in PT boat school he was assigned as instructor at the

Melville school. When Ned’s PT Boat was ordered out to sea he tried to get off

kite duty to join his boat. His skipper refused the request. The PT Boat was

lost with all hands.

Garber applied for and received a patent for the target kite on May 6. 1945. He sold half the rights to Stanley Potter in 1949 for one dollar. They looked into producing the kites commercially after the war, but discontinued the idea after being repeatedly told by manufacturers that they wouldn’t build the kites to Garber’s specifications because the kite would end up being too expensive and therefore wouldn’t sell. Rather then reduce the quality, Garber decided not to pursue it. The retail price in question was $15.

The Navy tried various ways to dispose of the 175,000 surplus kites after the war. The government sold the kites directly, for a while, for $2.79 in multiples of ten through the Office of Aircraft Disposal. Garber appeared in some advertisements as he, himself, tried to sell some of the surplus kites. Today, target kites sell on eBay for $150-$300.

As Paul returned to his work at the Smithsonian Institution, there were new challenges that needed to be solved. He had long since dedicated himself to the preservation of our nation’s aeronautical heritage by doing ‘whatever it took’ to get the job done. He was a master finagler! Paul personally convinced Lindbergh to give the ‘Spirit of St. Louis’ to the Smithsonian, and was successful in getting the ‘Wright Flyer’ back from Europe.

The storage of the museum’s historic aircraft collection had never been a problem in the past. The entirety of what Garber collected was either on display at the Arts and Industries Building or on loan to other museums. That was about to change.

At

the end of the war, General Hap Arnold and Senator Jennings Randolph thought it

was time the Smithsonian Institution had an Air Museum. As Garber worked

with them on the wording of the public law, General Arnold gave the order to

preserve one of each of all significant aircraft of World War II, as well as all

captured aircraft. The museum was established by order of Public Law number 722

of the 79th Congress, and was signed by President Truman on August 12th,

1946. In 1966 Congress changed the name to National Air and Space Museum.

At

the end of the war, General Hap Arnold and Senator Jennings Randolph thought it

was time the Smithsonian Institution had an Air Museum. As Garber worked

with them on the wording of the public law, General Arnold gave the order to

preserve one of each of all significant aircraft of World War II, as well as all

captured aircraft. The museum was established by order of Public Law number 722

of the 79th Congress, and was signed by President Truman on August 12th,

1946. In 1966 Congress changed the name to National Air and Space Museum.

Paul Garber became the first curator of the Smithsonian Institution’s Air Museum, eventually becoming Head Curator, and Senior Historian. He was officially retired by civil service requirements at the age of 70, but continued going into work on a regular basis well into his 92nd year as Historian Emeritus.

When Paul Garber took ownership of the huge collection of World War II aircraft from the U.S. Army Air Force, it was stored in an abandoned airplane factory in Chicago, now the site of O’Hare Airport.

The Navy also had a collection of historic aircraft for the Smithsonian collection, which was in storage at Norfolk, Virginia.

A crisis surfaced in 1952 when the Korean War forced the Navy to give to the US Air Force, the space that was being used to house the historic aircraft in Norfolk, Virginia.

Garber began to search for warehouse space near Washington, DC, so he could bring the Smithsonian’s entire collection of treasures home to the nation’s capital. It was a difficult search.

What does one do when faced with the problem of how to find space for a huge fleet of aircraft? One takes to the air, of course! That is exactly what Paul Garber did. He persuaded a pilot friend to take him up in his Piper J-3 so he could conduct an aerial survey of the Maryland and Virginia suburbs that surround the Washington area.

Finally, Garber found 21 acres in Suitland, Maryland (now Silver Springs, Maryland) that was controlled by the National Park and Planning Commission, who not only was convinced by Garber to turn it over to the Smithsonian, but they were even pleased about it.

Garber had excellent ‘scrounging’ abilities. Whether he was scrounging for old

aircraft, or, in the case of the new site in Maryland, he would bring out his

very famous powers of persuasion to secure needed services. Army engineers at

Fort Belvoir provided a bulldozer to clear trees, the Navy provided prefab

buildings at cost, local contractors dropped off unused cement at the end of the

day. “There was no budget!” he recalled to friends with pride.

Garber had excellent ‘scrounging’ abilities. Whether he was scrounging for old

aircraft, or, in the case of the new site in Maryland, he would bring out his

very famous powers of persuasion to secure needed services. Army engineers at

Fort Belvoir provided a bulldozer to clear trees, the Navy provided prefab

buildings at cost, local contractors dropped off unused cement at the end of the

day. “There was no budget!” he recalled to friends with pride.

Eventually the facility was named the Garber Hill Restoration Center at Silver Springs, Maryland. It is the restoration, renovation, and storage location for NASM. It is where the planes are prepared for display in the main Air and Space Museum.

Many of the famous planes on display today at the Smithsonian are the direct result of Paul’s finagling; known around the museum as the Garber method. He was often quoted as saying “I’ll beg, or do whatever is necessary to get the old, famous airplanes for display at the museum”. It was his passion and drive that was responsible for the Smithsonian Institution having assembled the most complete and impressive collection of historic aircraft in the world.

When the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum opened it’s own enormous freestanding location on the mall on July 1, 1976, Paul Garber, retired but active Historian Emeritus quipped, “It isn’t big enough.”

Garber’s spirit is also present at the new Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center located in northern Virginia near Washington Dulles International Airport. Finally, after many years of waiting, there is a unique collection of historic kites on view at the new Center.

This exhibit is the valuable contribution that it is today because of a collection Paul Garber made a priority since 1920. Garber began collecting kites as soon as he went to work for the museum 14 years after Professor Langley died. Langley, Secretary of the Institution, was interested in man-carrying kites. Garber knew his kite history; he was well aware that the innovators in aviation history tested their aerodynamic theories with kites.

Garber was quoted in a 1977 article with Valerie Govig as saying;

“ When I first came here (the Smithsonian Institution), I found, over in {Langley’s} old shop, several kites not complete. One was a very unusual triangular box kite cell, but the top surface had an airfoil, so he was using kites as a means of testing the lift of curved surfaces. Another one was an octagonal cell. Another one was a tri-plane, with extreme stagger—one of his experiments.”

Garber also enjoyed the detective work, and he was good at it. Paul called the Weather Bureau and they gave him one of the last kites they had in stock, a 1921 model.

Paul contacted William Eddy’s daughter after

finding her in California, and she gave him some original Eddy kites for the

museum. He was a very convincing and charming man.

Paul contacted William Eddy’s daughter after

finding her in California, and she gave him some original Eddy kites for the

museum. He was a very convincing and charming man.

Garber consulted with the Alexander Graham Bell museum in Baddeck Bay, Nova Scotia, when they first opened. As a thank you gift, the museum gave Paul 16 original cells from an early Bell tetrahedral kite for the Smithsonian Institution collection.

These historic and significant kites were added to the collection Paul had been putting together since 1920. The Smithsonian Institution kite collection included numerous historical kites as well as international kites from Turkey, Korea, Japan, Ceylon, Viet Nam, Philippines, China, and so many more. Now, they have much revered exhibit space in the Smithsonian Institution.

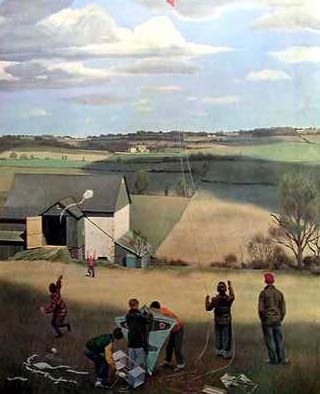

S. Dillon Ripley, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution in 1966 was walking on the National Mall (large grass area) with Paul Garber one summer day. Ripley was lamenting the lack of people using the Mall and asked Paul how he thought the use of the place could be increased. Garber answered that a kite contest would do it—he suggested a “Carnival of Kites”. “Good” said Ripley, “You are in charge”.

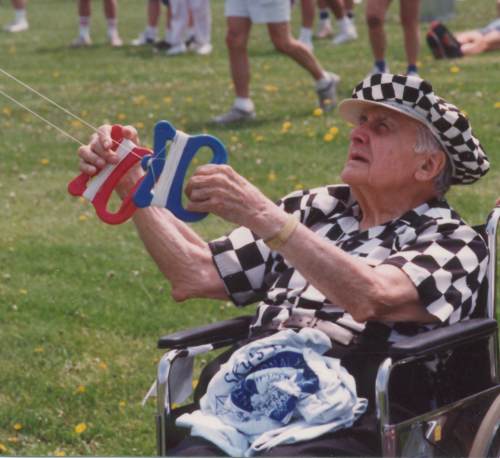

Paul and his wife Irene Garber became devoted to the annual springtime kite contest. It became their annual labor of love; their hardest, yet most pleasurable job. As Director of the Kite Carnival, Garber would stand on a platform in the center of the festivities, with microphone in hand, overflowing with joy. Garber was in his glory, kites surrounded him He was making decisions, telling stories, solving problems, and heaping praise on young competitors, even, at times, breaking into song.

Paul Garber died on September 23, 1992, at the age of 93, just four months after I saw him happily flying his target kite at the Niagara Falls International Kite Festival in May of that year. This was the second time I had met him and I am honored to have had the opportunity to spend so much time with him.

Garber received many citations, awards and medals, but the medal and citation the Secretary of the Smithsonian, S. Dillon Ripley gave to Paul Garber on February 28, 1969 was especially poignant. The certificate read:

“For exceptional service as Flyer, Historian, Collector, Conservator, Educator. In recognition of half a century devoted to the increase and diffusion of knowledge of the history of flight”

Paul Garber was a national treasure.

The Annual Smithsonian Kite Festival continues every year with loyal and dedicated volunteers. This year the kite competition is on Saturday March 27, 2004 on the National Mall. There are two additional family kite days planned by the Smithsonian. March 13th at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center and March 20th at the National Air and Space Museum on the National Mall.

Anyone interested in learning more about Paul Garber’s target kites should go to Charles Hall’s web site at www.rtpnet.org/robroy/targetkites/

It has a wealth of information and is a terrific source.

References:

Newspapers:

Niagara Gazette May 1992

Washington Star 1964

Books:

Kite Craft: The History and Process of Kitemaking Throughout the World

By: Lee Scott Newman and Jay Hartley Newman

Flying Kites in Fun, Art, and War

By: James Wagenvoord

The Complete World of Kites

By: Bill Thomas

Magazines:

Spalding Sportsman, January 1945 Hit a Kite – Bag a Plane

Popular Science, May 1945 Target Kites Imitate Planes Flight

By: Arthur Grahame

Kitelines, Spring 1977 Paul Garber Man About Kites at the Smithsonian

By: Valerie Govig

Smithsonian Magazine, May 1997 Smithsonian Perspective: Patriarch of Flight- Paul Garber

By: I. Michael Heyman

Web Sites:

www.rtpnet.org/robroy/targetkites

© M. Robinson, 2004